Every year I make my girlfriend a birthday card. The twist is that I make it as a single page website that I send to her on the day.

I do this because I love tailwind utility classes it’s easy to personalise, it’s something that I can inject some creativity into, it’s something that she can look back on.

Typically I spread the site over 2 mornings: one for the general layout and most of the code, then an hour or so to review and add relevant pictures. We are not here sitting writing production code, we are creating websites that look like this:

Spinning avocados, dogs and clouds.

It’s simple, it’s stupid, it’s somewhat optimised for different devices, and the code is…bad. Not “quit programming now” bad, but the kind of code that knows it will never need to be maintained, that needs to be written quickly and that I can’t justify spending days on to get every small detail right.

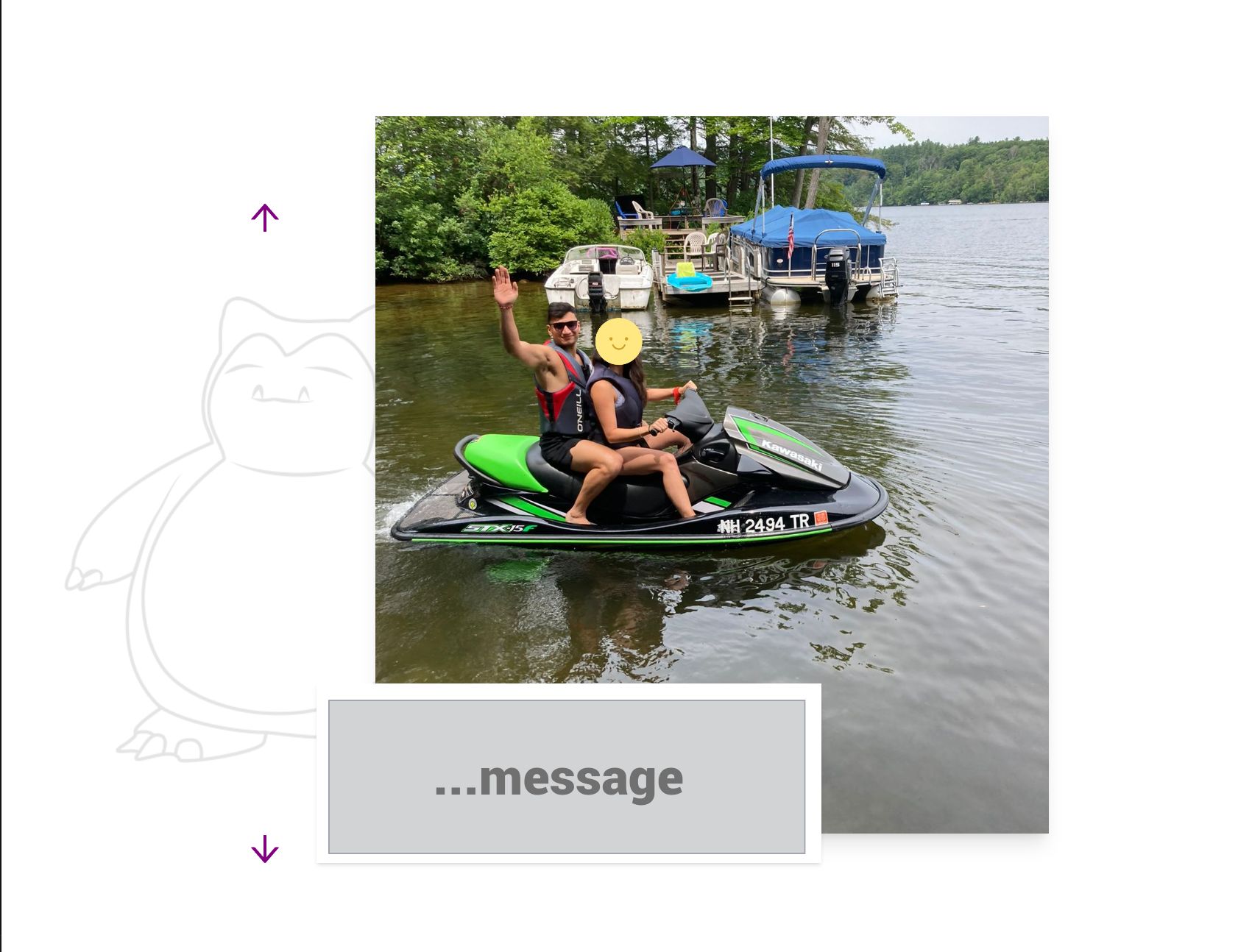

I did make efforts to make a more ‘stylish’ website, the below is a react SPA from last year, with animations, transitions, hover effects and layered images (I even bought a custom domain):

This past year though, I realised that so much of that stuff didn’t matter.

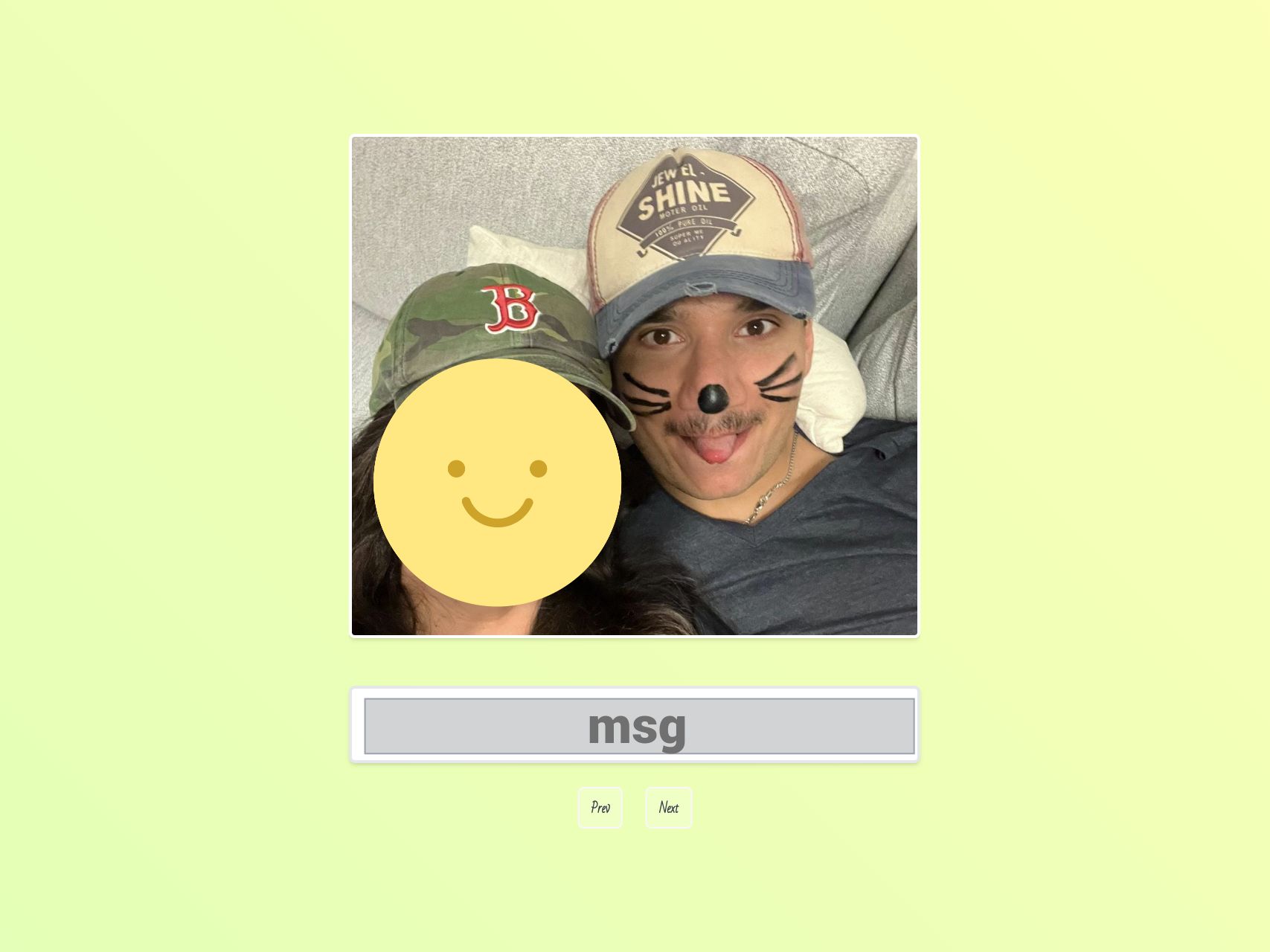

I made a simple app, helped in a big way with Chat GPT, and matched a picture, a song and a message together with a next/prev button. There’s a randomly generated pastel background and some simple responsiveness so she can share the card with her family and friends on all devices. It’s deployed on netlify with a simple {name}-{age}.netlify.app:

The parts of these websites that my girlfriend love are the humour, the personalisation (images, thoughtful messaging, music) and the fact that the website is something she can share and look back on.

The parts of these websites that make minimal to no difference include: clean code, optimising page loads, fancy layouts, fancy animations. A lot of these things are in the “fancy” website I did last year, and when I mention them she definitely notices and appreciates the attention to detail, but what’s interesting to me is that taking these things away doesn’t impact the core part about the card that delights her.

Focus on the kernel

I’d go so far as to say, in terms of delivering a “product” that is loved by its users, these cards are right up there as the best things I have ever shipped.

And it’s pretty obvious why:

- I built the app with a crystal clear understanding of who are my users.

- I focused entirely on delivering what I know my user wanted.

- I spent minimal to no time delivering what I know my user doesn’t care about.

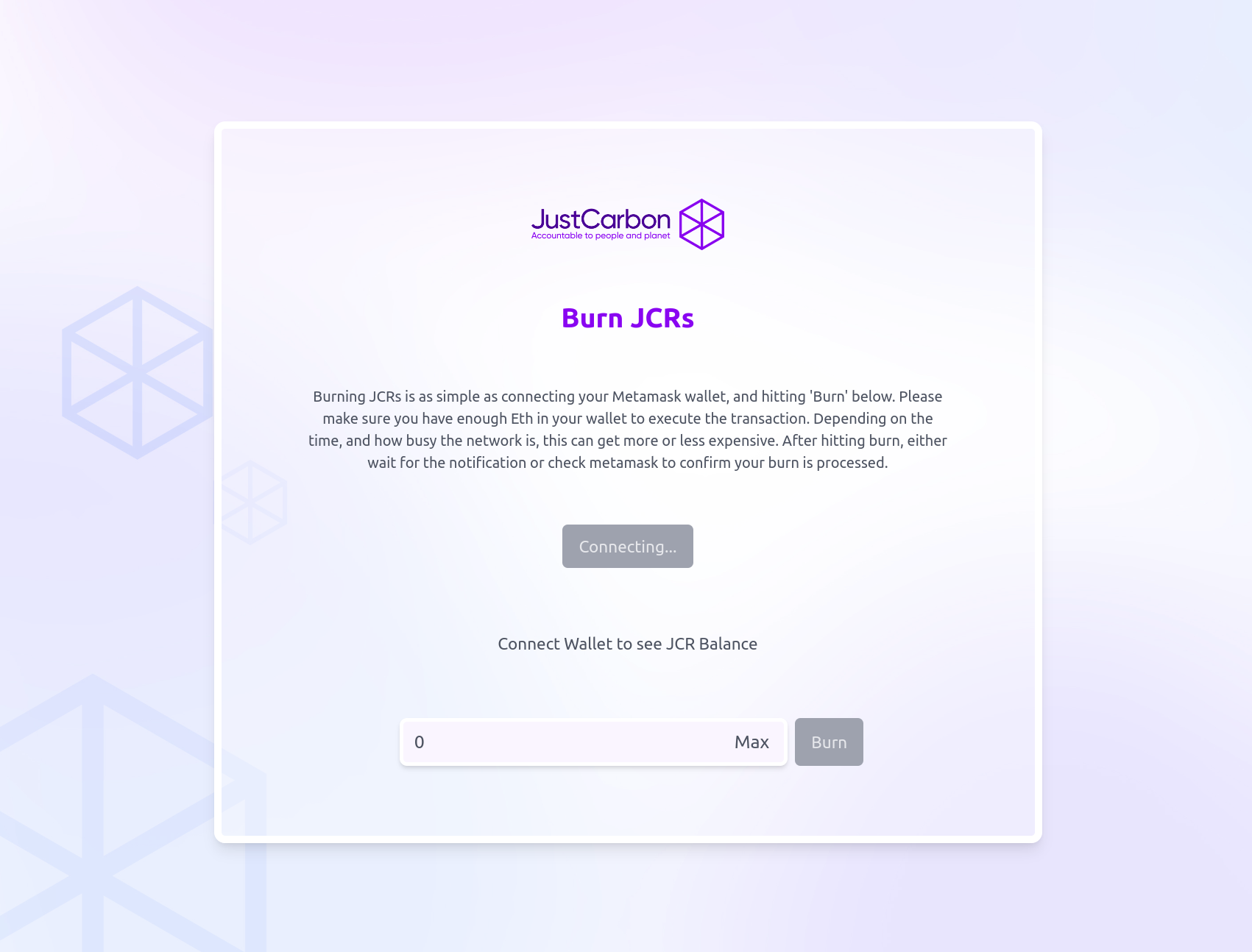

Another example was a simple applet I whipped up towards the end of a contracting engagement. This was a NextJS DApp for the Justcarbon foundation, it connects to Metamask and is deployed to AWS Amplify. I actually made this in an evening as a very simple way to call the burn() function for carbon tokens.

I knew the team needed to do this, and until now they were trying to figure their way around etherscan to call the contract directly.

I originally wanted to demonstrate a prototype of using NextJS to create a DApp. My surprise came from how well this app was received by the team, and how they still used it months later as a convenient and more user friendly alternative to etherscan.

Again, I had a very clear idea of who I was building for (the team) and shipped something quickly that met exactly that need. I didn’t have time to add a lot of complexity, yet it still delighted the people who used it to the extent that, when I turned off the AWS Amplify app - assuming nobody was still using this simple prototype - I got a message a couple of days later asking where the application had gone.

Yes, we have a name for that…

I don’t want to overfit the message here. Obviously, we introduce standards and production quality code because we want to build applications that will grow and scale with more developers and users than the handful of people the above examples will ever serve.

I’m also aware that creating an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) is a cornerstone of startup culture and it’s not exactly novel to be articulating it here.

Instead it comes back to lived experience. I conceptually understood the MVP strategy when I first read The Lean Startup, but examples like the above really drive home what an MVP actually is, and just how minimum it really can be.

I think we get so caught up in techno-fetishism and fear of judgement that we are afraid to ship. I’m certainly guilty of this. I worry what people will think of me if I show them code that is less than perfect, or a product that lacks polish, or a github repo that is lacking high test coverage. The above are crucial once you know you’re building out something people love, but the above also slow you down.

Takeaways

I want to ship more ideas and less code over the next few months. I have a number of ideas floating in my head that I would like to test. The above examples are motivating me to JFDI.

I don’t want to write bad code, but I don’t want to obsess about code quality at the expense of getting my ideas out there. I want to test things, and if that means creating a throwaway proof of concept that can be discarded or reworked later, so be it.