In this first challenge we will review of a number of super important foundations when dealing with assembly. We’re going to cover a decent chunk of ground here but by the end, we should have a good grasp of what actually happens at the bytecode level when we send a call to a contract.

Topics Covered

- Reading Bytecode instructions

- Writing our first lines of assembly

The challenge:

Our challenge is the MagicNumber contract:

To solve this level, you only need to provide the Ethernaut with a Solver, a contract that responds to

whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()with the right number… …The solver’s code needs to be really tiny. Really reaaaaaallly tiny. Like freakin’ really really itty-bitty tiny: 10 opcodes at most.

Sounds interesting. What does the contract look like?

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract MagicNum {

address public solver;

constructor() {}

function setSolver(address _solver) public {

solver = _solver;

}

}Simple enough. Let’s setup our test:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import "forge-std/Test.sol";

import "../src/MagicNum.sol";

contract ASMMagicNum is Test {

MagicNum public target;

function setUp() public {

target = new MagicNum();

}

function testAttackMagicNum() public {

// fetch the solver from the MagicNum contract

address solver = target.solver();

// ensure that the code length is 10 bytes

assertLe(solver.code.length, 10);

// call solver with "whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()"

(, bytes memory data) = solver.call(abi.encodeWithSignature("whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()"));

// decode the data and check it's correct

uint256 decoded = abi.decode(data, (uint256));

assertEq(decoded, 42);

}

}Our test is pretty simple:

We setup the contract, then grab the solver from the contract and validate that the code length is, in fact, less than or equal to 10 bytes. Finally we call the address stored there with whatIsTheMeaningOfLife() and check the data is equal to 42.

Below 10 bytes

If we try and solve this in solidity, the solution might look like:

contract Solver {

function whatIsTheMeaningOfLife() external pure returns (uint) {

return 42;

}

}

contract ASMMagicNum is Test {

// ...

function testAttackMagicNum() public {

target.setSolver(address(new Solver()));

address solver = target.solver();

// ...

}

}Above we’re creating a new Solver contract that has a method whatIsTheMeaningOfLife() that returns 42. We then set the solver to the address of this contract and call it - boom - we’re done. Let’s run the test and find out.

forge test --match-test testAttackMagicNum[FAIL. Reason: Assertion failed.] testAttackMagicNum() (gas: 100157)

Logs:

Error: a <= b not satisfied [uint]

Value a: 119

Value b: 10Our test (predictably) fails: the code length is 119 bytes, not 10 or less, as the check requires. So how do we get it down to 10?

Actually, come to think about it… how do we even deploy bytecode to an address?

Cheating a bit

One option for us is to use one of foundry’s inbuilt “cheat codes” so we can start working on the solution.

Cheat codes alter the state of the VM in tests in ways we can’t do in the EVM. They are useful for tests and simulations, and can save us some time.

(Don’t worry - by the end of this article we will do things the “proper” way)

vm.etch is a nifty little cheatcode that allows us to write arbitrary data to an address. This will allow us to write a raw bytecode solution without having to run through contract creation (yet). It takes 2 arguments:

- The address to write to

- The hexadecimal data to write

We can add it to our test in 2 lines, first we define a variable solverBytecode:

contract ASMMagicNum is Test {

MagicNum public target;

// here we can put whatever code we want, the ffffff is just random data

bytes solverBytecode = hex"ffffff";And let’s use the cheatcode in our test

function testAttackMagicNum() public {

address solver = target.solver();

vm.etch(solver, solverBytecode);

// ensure that the code length is 10 bytes

assertLe(solver.code.length, 10);Running our test command gives the new log:

[FAIL. Reason: EvmError: Revert] testAttackMagicNum() (gas: 9079256848778899555)

Traces:

[9079256848778899555] ASMMagicNum::testAttackMagicNum()

├─ [2325] MagicNum::solver() [staticcall]

│ └─ ← 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

├─ [0] VM::etch(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000, 0xffffff)

│ └─ ← ()

├─ [0] 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000::whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()

│ └─ ← "EvmError: StackUnderflow"

└─ ← "EvmError: Revert"

Test result: FAILED. 0 passed; 1 failed; finished in 463.39µsSo we’re getting a new error and we can see that 0x000... is actually being called. This shows us we’ve made it past the code length check, but we’re still not quite there.

Let’s breakdown what’s actually going on here - what does StackUnderflow mean?

(You might see 650500c1() in place of whatIsTheMeaningOfLife(), we will touch on all this in another post).

What’s going on?

When we call the solver address, the EVM does nothing more than execute the code that exists at that address, with the calldata passed to it.

In our case, the following steps happen:

- We haven’t set a solver yet, so

target.solver()returns the default value ofaddress(0x0) - We have stored the bytecode

0xffffffatsolver(address(0x0)) usingvm.etch address(0x0)is called with the signature"whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()"and no additional calldata.

Usually, when we call a contract in solidity, the compiled contract will check that the function whatIsTheMeaningOfLife() exists, and revert if it does not. This is typically achieved using a jumptable embedded into the contract bytecode (JUMP, JUMPI and JUMPDEST being the relevant opcodes you will see in most contracts).

In our case, we don’t have any of that. Instead we have 0xffffff, which can be written as 3 bytes of the opcode 0xFF/SELFDESTRUCT

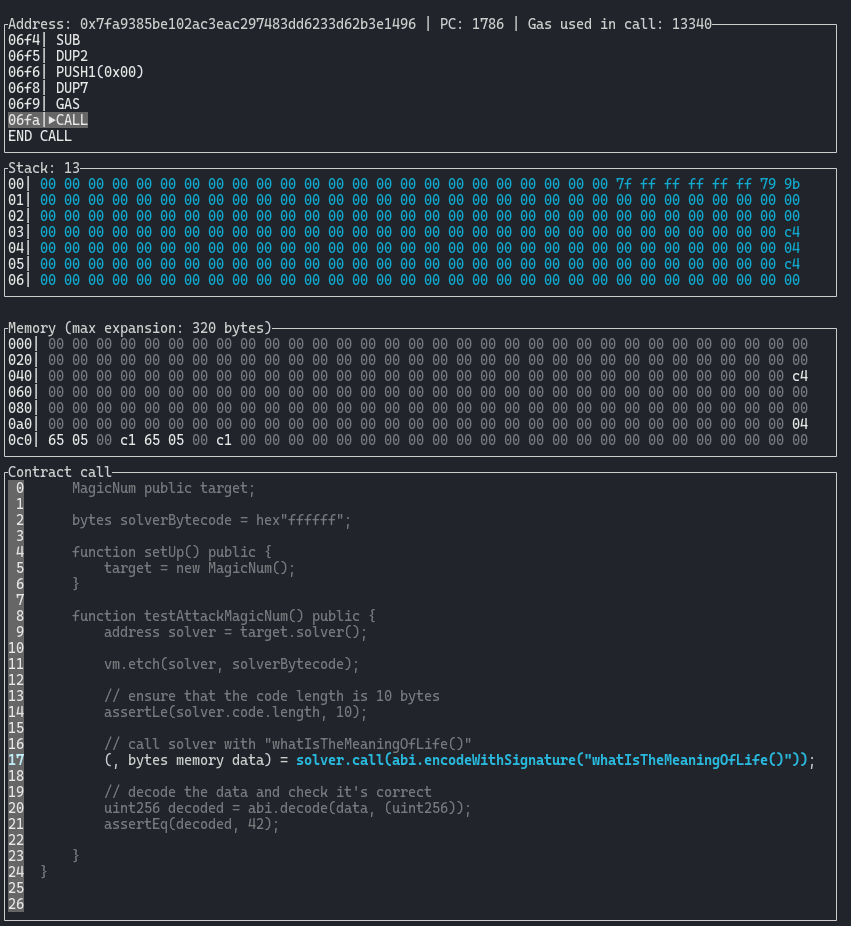

We can check this by stepping into the foundry debugger. This is a handy tool that will show us the individual steps of the EVM as it executes our contract:

forge test --debug testAttackMagicNumThe debugger will walk you line by line through the contract execution, keep moving until you get to the spot in the image below.

This is the state of the EVM as right before we call our solver contract. We can see the address (0x7fa...) of our calling contract, the stack, memory and where we are in the solidity code:

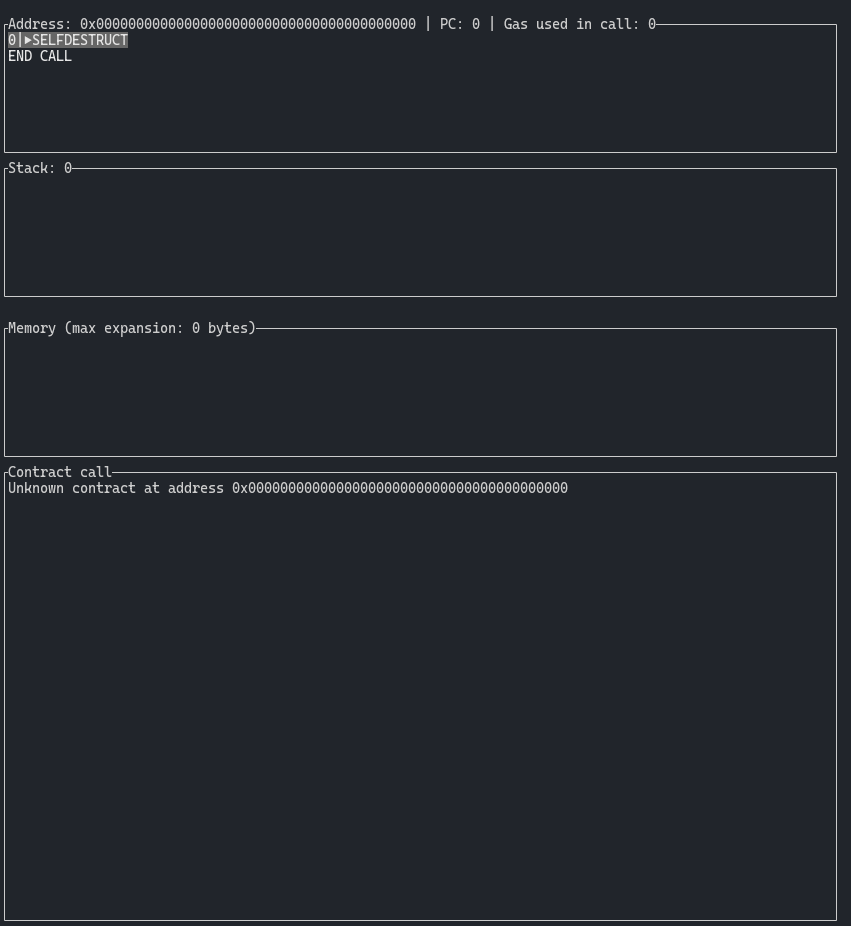

Advancing one more step, and this is what it looks like when we are calling our solver contract. Notice that we have an empty stack, nothing in memory, and that we are at the zero address. We have an ‘unknown contract’ because we are executing pure bytecode.

There’s only one OPCODE at the top: 0xff - SELFDESTRUCT.

If we check the info for SELFDESTRUCT we can see that it takes 1 argument - Stack input:

address: account to send the current balance to

So the first SELFDESTRUCT call is expecting an address, specifically, it’s expecting this address from the stack.

But we have pushed nothing TO the stack, hence the StackUnderflow error we saw above.

So we can see now that any bytecode we write to the solver address will be executed, but we need to be careful to make sure it executes as we expect.

An actual solution

What we want to do is actually really simple:

When the address stored in target.solver is called, return the number 42.

A good place to start is how we can return a value in bytecode.

Let go back to our friend EVM Codes, this time for the RETURN OPCODE

Straight away we can see that RETURN expects 2 arguments from the stack:

- offset: byte offset in the memory in bytes, to copy what will be the return data of this context.

- size: byte size to copy (size of the return data).

Offset

Offset just means “place in memory to start reading from”.

Recall how memory is stored in the EVM: it’s a giant array that is wiped between contract calls. We can store whatever data we want in there, and we can fetch it by starting at the offset, then reading the next size bytes.

Examples (spaces added for readability):

# Offset 0x00

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

^

# Offset 0x04

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

^(Remember that the offset in our case is in bytes, which are represented by 2 hex characters.)

Size

Size is very simple: starting from the offset, it just represents how many bytes to return, so if your data, starting at offset 0x02 is DEADC0FFEE00000000000..., size of 0x01 will return 0xDE, while size of 0x05 will return 0xDEADC0FFEE.

Putting it together

The EVM is a stack machine, so the OPCODE RETURN will take its arguments sequentially, from the top of the stack. Meaning we need the stack to look like:

0 | OFFSET

1 | SIZEWe will therefore need to make sure that, at the offset, the number 42 / 0x2a is stored in Memory at the offset that we choose.

Storing in Memory

Memory has 2 opcodes for storage MSTORE and MSTORE8.

Both take 2 arguments, an offset (which we discussed above) that says where in memory to store the data, and a value argument.

For MSTORE the value will be left padded and stored as a full 256 bit word, for MSTORE8 the value is stored as an 8 bit value.

When we return the value, the data will be read as a full 256 bit word. So if we’re just returning a single number, it will need to be encoded like so:

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 002a

^^

42You might notice that there are 2 ways to do this:

- MSTORE the value

0x2astarting at offset zero - MSTORE8 the value

0x2astarting at offset0x1f(31 bytes)

Here’s a link to the EVM Playground to demonstrate

Doesn’t matter enormously which one you prefer for this exercise.

Bytecode Solution

Let’s write our bytecode.

60 is the opcode for PUSH1. It takes the next byte and pushes that byte to the top of the stack.

We start with the above: we store 0x2a as the last byte in a 32 byte word. 0x1f = 31 in hex.

60 2a // PUSH1 VALUE (0x2a = 42)

60 1f // PUSH1 MEMORY OFFSET (31 bytes)Our stack should now look like:

0 | 0x1f

1 | 0x2aWe can now store the value 0x2a at offset 0x1f using MSTORE8:

53 // MSTORE8 (offset, value)This will empty the stack and move the value into memory.

Lastly, we need to return it with opcode f3 as above.

60 20 // PUSH1: RETURN DATA SIZE (32 bytes)

60 00 // PUSH1: MEMORY OFFSET (0 bytes)

f3 // RETURN (offset, size)Hopefully, after the above, that’s not too scary.

Put together we have the full bytecode 602a601f5360206000f3 - a perfect 10 bytes!

Let’s give this a whirl and see what happens!

contract ASMMagicNum is Test {

MagicNum public target;

bytes solverBytecode = hex"602a601f5360206000f3";

// ... rest of the contract

}Run it with full logging to see the stack trace:

forge test --mt testAttackMagicNum -vvvvvRunning 1 test for test/MagicNum.t.sol:ASMMagicNum

[PASS] testAttackMagicNum() (gas: 13766)

Traces:

[104173] ASMMagicNum::setUp()

├─ [49699] → new MagicNum@0x5615dEB798BB3E4dFa0139dFa1b3D433Cc23b72f

│ └─ ← 248 bytes of code

└─ ← ()

[13766] ASMMagicNum::testAttackMagicNum()

├─ [2325] MagicNum::solver() [staticcall]

│ └─ ← 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

├─ [0] VM::etch(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000, 0x602a601f5360206000f3)

│ └─ ← ()

├─ [18] 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000::whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()

│ └─ ← 0x000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000002a

└─ ← ()

Test result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; finished in 292.50µsTest passed! That’s great news!

If you want to see the contract step-by-step, call forge test --debug testAttackMagicNum to see the stack, memory and contract in action.

Interestingly enough, we can see in the logs that the function whatIsTheMeaningOfLife() was called and returns 42 / 0x2a even though we didn’t specify any functions in our bytecode. As mentioned earlier - normally solidity will compile our bytecode with JUMP logic for different defined functions (more on these in other sections) and REVERT if nothing was found. In our case no matter what we call the function will return 42. Try it for yourself.

Let’s take a break for a minute - we still need to remove the forge cheatcode vm.etch, but this post is getting long enough. Grab a coffee, take a walk, go touch some grass. See you in the next one.