In the last part, we attempted to solve the MagicNumber contract, by writing raw bytecode directly to an address using a foundry cheatcode. In this article, we remove the dependency on foundry, and deploy the contract bytecode ourselves.

Topics Covered

- Creating contracts using Assembly

- Reading from storage and our first line of Yul

Recap

Let’s take a second to recap where we got to, here is the MagicNumber.sol contract, we’re trying to make a solver contract return the number 42, where solver must have a code length of 10 bytes or less:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

contract MagicNum {

address public solver;

constructor() {}

function setSolver(address _solver) public {

solver = _solver;

}

}Here is the state of our test so far:

pragma solidity ^0.8.0;

import "forge-std/Test.sol";

import "../src/MagicNum.sol";

contract ASMMagicNum is Test {

MagicNum public target;

bytes solverBytecode = hex"602a601f5360206000f3";

function setUp() public {

target = new MagicNum();

}

function testAttackMagicNum() public {

address solver = target.solver();

vm.etch(solver, solverBytecode);

assertLe(solver.code.length, 10);

(, bytes memory data) = solver.call(abi.encodeWithSignature("whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()"));

uint256 decoded = abi.decode(data, (uint256));

assertEq(decoded, 42);

}

}Our test sets up a fresh instance of the contract. It then grabs the hex literal 602a601f5360206000f3 and writes to the address returned by target.solver(). We check to see if the bytecode is less than or equal to 10 bytes and if so, we call the method “whatIsTheMeaningOfLife” and check the returned data is equal to 42.

Cheating a bit

We’ve been using foundry’s vm.etch cheatcode to write the contract bytecode to an address. This simplified things up until now, but it’s not something that’s possible outside of the test environment. We need to remove it.

In order to remove Etch, we will have to deploy our bytecode. This means we need to create a contract, and fetch the deployed address.

CREATE

CREATE is a bit of a mouthful when you first read it:

Creates a new contract. Enters a new sub context of the calculated destination address and executes the provided initialisation code, then resumes the current context.

In simple english, this just means that CREATE runs whatever code you pass to it. The whole part about context is telling us that the code run before we call CREATE is executed separately to the code we run DURING the CREATE process.

Specifically, the code that we pass to CREATE must also RETURN the bytecode we want to deploy.

As a worflow then, we need to:

- Call CREATE

- CREATE runs the passed code (“contract creation bytecode”)

- The contract creation bytecode returns some more code (“runtime bytecode”)

- The CREATE opcode deploys the returned code at a new address.

- The CREATE opcode then sends the address back to the caller.

The creation bytecode is discarded once CREATE is run - this is the bytecode that contains the constructor logic in smart contracts. Once run, only the runtime bytecode is stored onchain.

Arguments

If we look at the arguments to CREATE, we have 3 Inputs from the Stack:

- value: value in wei to send to the new account.

- offset: byte offset in the memory in bytes, the initialisation code for the new account.

- size: byte size to copy (size of the initialisation code).

So CREATE, similarly to RETURN, is reading from memory. We therefore need to load our contract bytecode into memory first:

69 602a601f5360206000f3 // PUSH10 (runtime bytecode) (see below)

60 00 // PUSH MEMORY OFFSET (0 bytes) to return from

52 // MSTORE (offset, value) the bytecode at position zeroHopefully this is fairly self explanatory at this point. The runtime bytecode is just taken from above and we store it as a single 32 bytes word, left padded, starting at the zero offset in memory.

For RETURN, it’s similar:

60 0a // PUSH1 RETURN DATA SIZE (10 bytes - bytecode len)

60 16 // PUSH1 MEMORY OFFSET (22 bytes - offset for padding)

f3 // RETURN (offset, size)The only thing to remember here is that, because we used MSTORE, the bytecode is loaded with 22 bytes of zero padding

Trying to Solve

See what happens when you replace the bytecode with the bytecode above:

bytes solverBytecode = hex"69602a601f5360206000f3600052600a6016f3";It should fail because now the bytecode is too long. We need 10 bytes, but we’ve added the creation bytecode and are still writing the whole thing to the solver address. We still need to call CREATE somewhere, and for that we need to move to inline assembly…

CREATE in Yul

We’re now ready to write some assembly in the Yul language, versus raw bytecode.

What we need to do is:

- Take our bytecode saved in contract storage

- Save it to memory

- Fetch the length of our data

- Call

createand pass it the correct length of our data - Save the address of the created contract and set the solver

1. Getting our bytecode data from storage

Recall that all contract variables are stored in a contract’s own storage slots. Contract storage is a big topic, but the following points are relevant for us:

- Slots start at slot 0

- Slots are 32 bytes in size

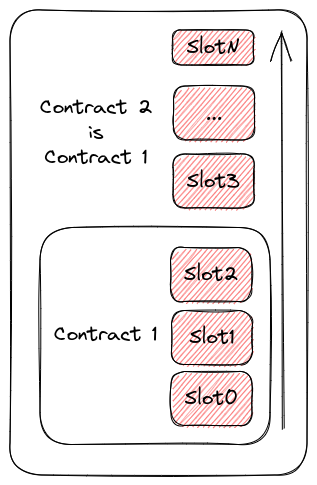

- If a contract inherits another contract, the child contract’s slots start after the parent contract’s slots end:

In our case, bytecode data is stored as bytes type in the storage variable solverBytecode. Bytes is a dynamic type, with complex storage rules that we aren’t going to go into here. What we need to know is that when working with less than 32 bytes, the data will be stored in the storage slot.

We can fetch this very simply in Yul assembly:

function testAttackMagicNum() public {

assembly {

// we know there are less than 32 bytes so the data in the slot is the bytecode

let data := sload(solverBytecode.slot)

}Here, we are calling the SLOAD opcode, which will return the full 32 bytes of data in the passed storage slot, and saving it in our data variable, which we have declared with the let data := assignment.

You’ll notice that, in Yul, we don’t manipulate the stack directly, the compiler is still around and will make sure the solverBytecode.slot is passed to SLOAD, and that the variable data is properly managed. Already we can see that Yul/Inline assembly offers a number of advantages versus writing raw, EVM bytecode!

2. Saving our bytecode data to memory

We already covered the opcode MSTORE in bytecode, its Yul counterpart is very similar; pass it a memory location and the data we want to store:

assembly {

let data := sload(solverBytecode.slot)

// save the data

mstore(0x00, data)

}3. Getting our data length

We know our data is 19 bytes or 0x13 long. Yul let’s us hardcode this and it would work just fine.

Alternatively, the EVM encodes the length of bytes data as the last byte in the array.

Put another way: our data length can be directly fetched from the data itself.

The code to do this is to use a bitwise AND on just the last byte. AND takes 2 values and returns 1 for a the resulting binary value only if BOTH binary values are equal to 1, for example:

>>> 0x13041313944093

100110000010000010011000100111001010001000000 | 10010011

>>> 0xff |

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 | 11111111

>>> 0x13041313944093 & 0xff |

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 | 10010011

^

data past here is removedFor us, if we just want the last byte, we can call and(data, 0xff) to fetch the length of our bytecode:

assembly {

// we know there are less than 32 bytes so the data in the slot is the bytecode

let data := sload(solverBytecode.slot)

// length of the data is stored at the end of the slot in the last byte

// we can fetch with a bitwise AND using a mask over the final byte

let len := and(data, 0xff)

}Final call

All that’s left is to call create and save the address:

// define the address here so we can access it outside of the assembly block

address _solver;

assembly {

// we know there are less than 32 bytes so the data in the slot is the bytecode

let data := sload(solverBytecode.slot)

// length of the data is stored at the end of the slot in the last byte

// we can fetch with a bitwise AND using a mask over the final byte

let len := and(data, 0xff)

// we can pass the memory start offset and length to the create opcode

// which will create a new sub context and return us the address where the init bytecode is deployed

_solver := create(0, 0x00, len)

}

// now set the solver to our created address

target.setSolver(_solver);

// ... rest of the testRun forge test on the contract and check the logs:

[65569] ASMMagicNum::testAttackMagicNum()

├─ [2018] → new <Unknown>@0x2e234DAe75C793f67A35089C9d99245E1C58470b

│ └─ ← 10 bytes of code

├─ [22402] MagicNum::setSolver(0x2e234DAe75C793f67A35089C9d99245E1C58470b)

│ └─ ← ()

├─ [325] MagicNum::solver() [staticcall]

│ └─ ← 0x2e234DAe75C793f67A35089C9d99245E1C58470b

├─ [18] 0x2e234DAe75C793f67A35089C9d99245E1C58470b::whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()

│ └─ ← 0x000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000002a

└─ ← ()Congratulations. That was a long one but you made it!

You’ll notice we are still calling setSolver(_solver) using solidity. This post was getting way too long as it is, so let’s leave calling contracts for another day but, you are welcome to try implementing yourself!

Till next time anon.